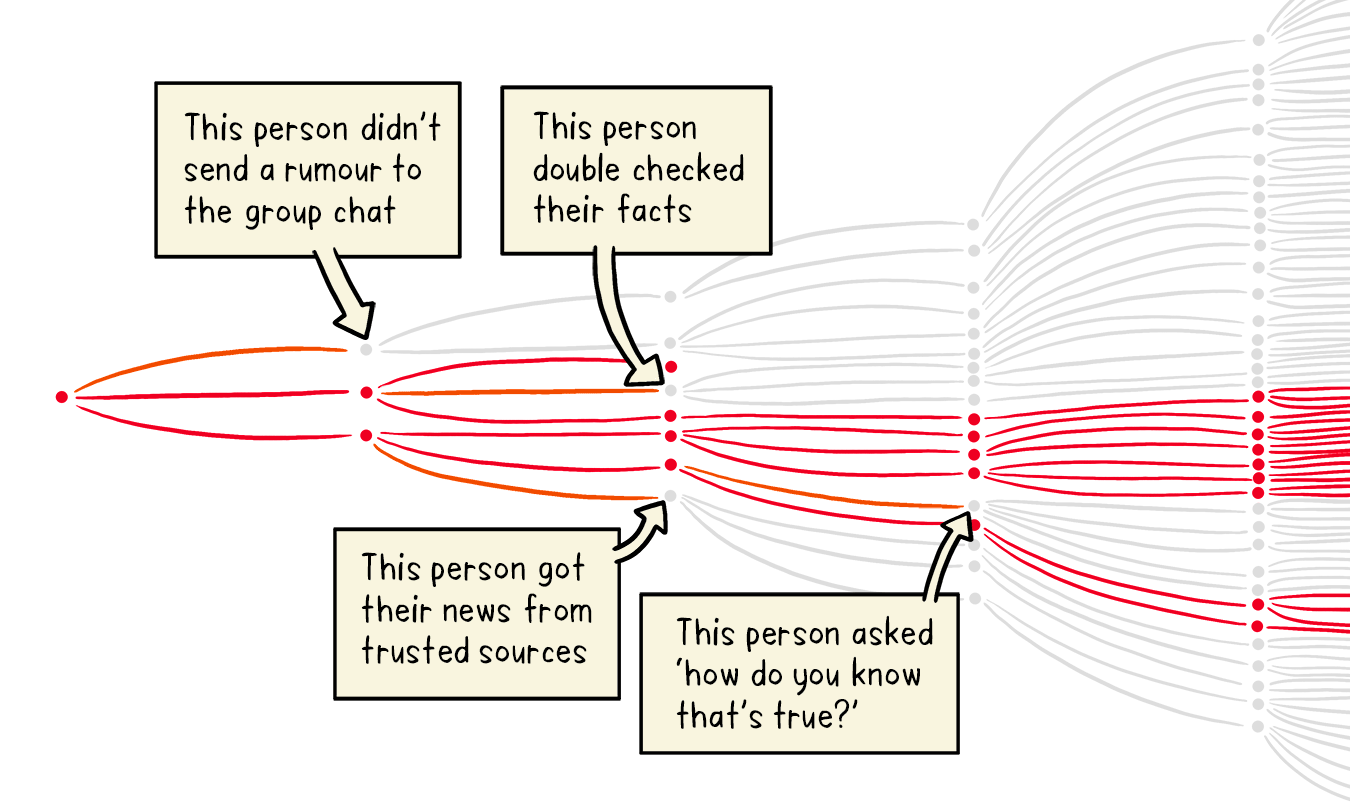

It helps to think of misinformation and disinformation spreading in the same way as viruses. One person might share fake news with their friends and family, and then a handful of them share it with more of their friends and family, and before you know it, potentially harmful or dangerous information is taking over everyone’s newsfeed.

But just as we can protect against COVID-19 with hand washing, physical distancing and masks, we can slow down the spread of misinformation and disinformation by practising some information hygiene. Before sharing something, ask yourself these questions:

How does this make me feel?

Why am I sharing this?

How do I know if it’s true?

Where did it come from?

Whose agenda might I be supporting by sharing it?

If you know something is false, or if it makes you angry, don’t share it to debunk it or make fun of it. That just spreads the misinformation or disinformation further. Learn more about how you can report misinformation online.

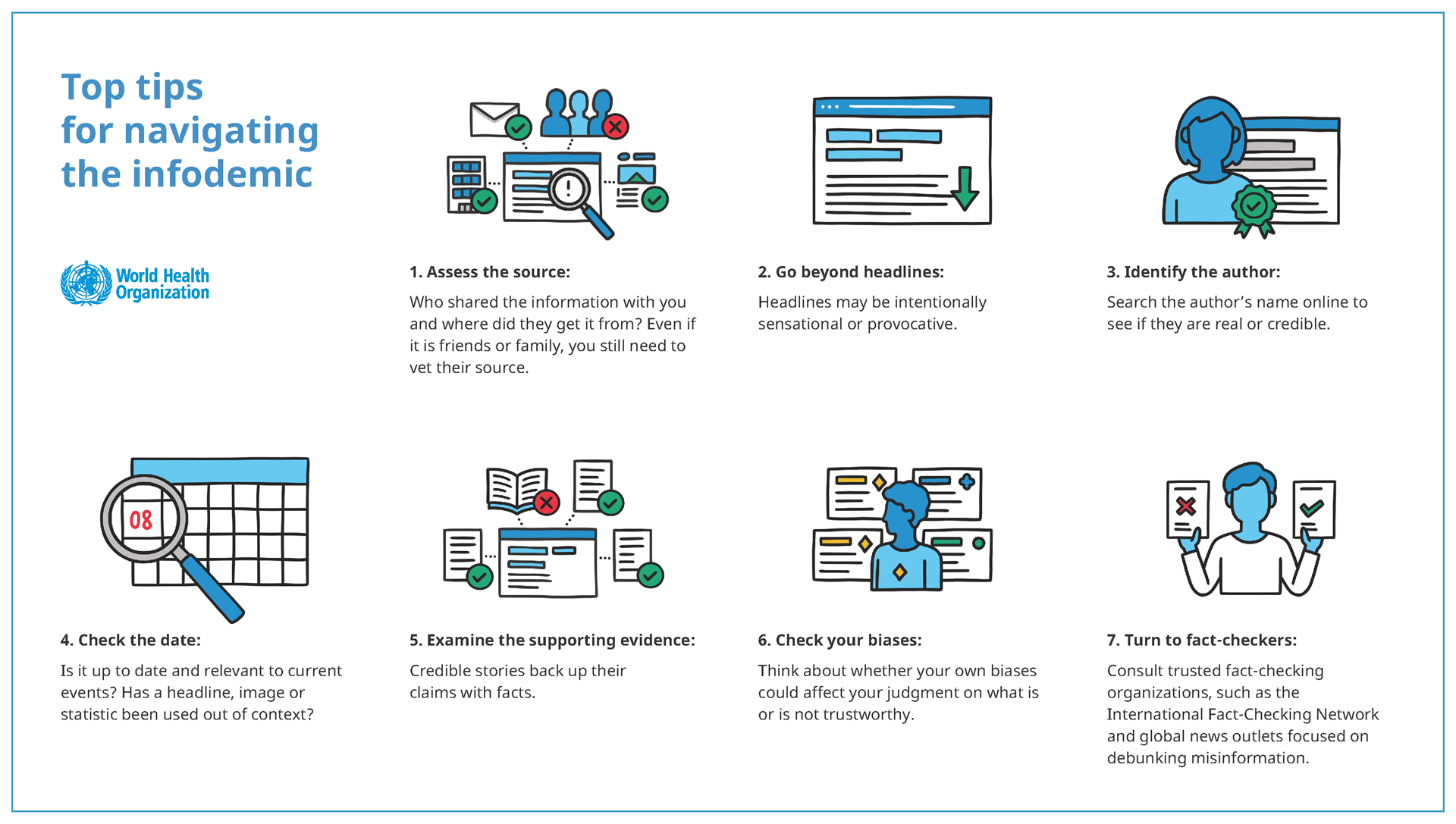

Good places to go for reliable information are the websites of your national Ministry of Health or the World Health Organization. Remember, though: information will change as we learn more about the virus.

WHO has developed guidance to help individuals, community leaders, governments and the private sector understand some key actions they can take to manage the

COVID-19 infodemic.

For instance, WHO has been working closely with more than 50 digital companies and social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, TikTok, Twitch, Snapchat, Pinterest, Google, Viber, WhatsApp and YouTube, to ensure that science-based

health messages from the organization or other official sources appear first when people search for information related to COVID-19. WHO has also partnered with the Government of the United Kingdom on a digital campaign to raise awareness of misinformation around COVID-19 and encourage individuals to report false or misleading content online. In addition, WHO is creating tools to amplify public health messages – including its

WHO Health Alert chatbot, available on WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Viber –

to provide the latest news and information on how individuals can protect themselves and others from COVID-19.

A version of this content originally ran on The Spinoff and has been adapted for use by WHO under creative commons.