Measles used to be common in Nepal.

“When I trained as a paediatrician, we would go to the local hospital to study measles,” says Professor Dr Shrijana Shrestha. “There were always children with measles in the wards.”

Professor Dr Shrijana Shrestha is a professor of paediatrics in Kathmandu. She says it's rare to see a child with measles anymore. "My students have only seen photos of measles, never a live measles case." (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Today, Professor Dr Shrestha, a paediatrician and professor in Kathmandu, says her students learn about measles from textbooks. “They’ve seen photos of children with measles, but no actual cases.”

Her colleague, Professor Dr Imran Ansari, says he can’t remember the last time Patan Hospital, where he is the Medical Director, admitted a child with confirmed measles. “It may be years,” he says. “There have been children with fever and rash and we report those, but none have been confirmed measles.”

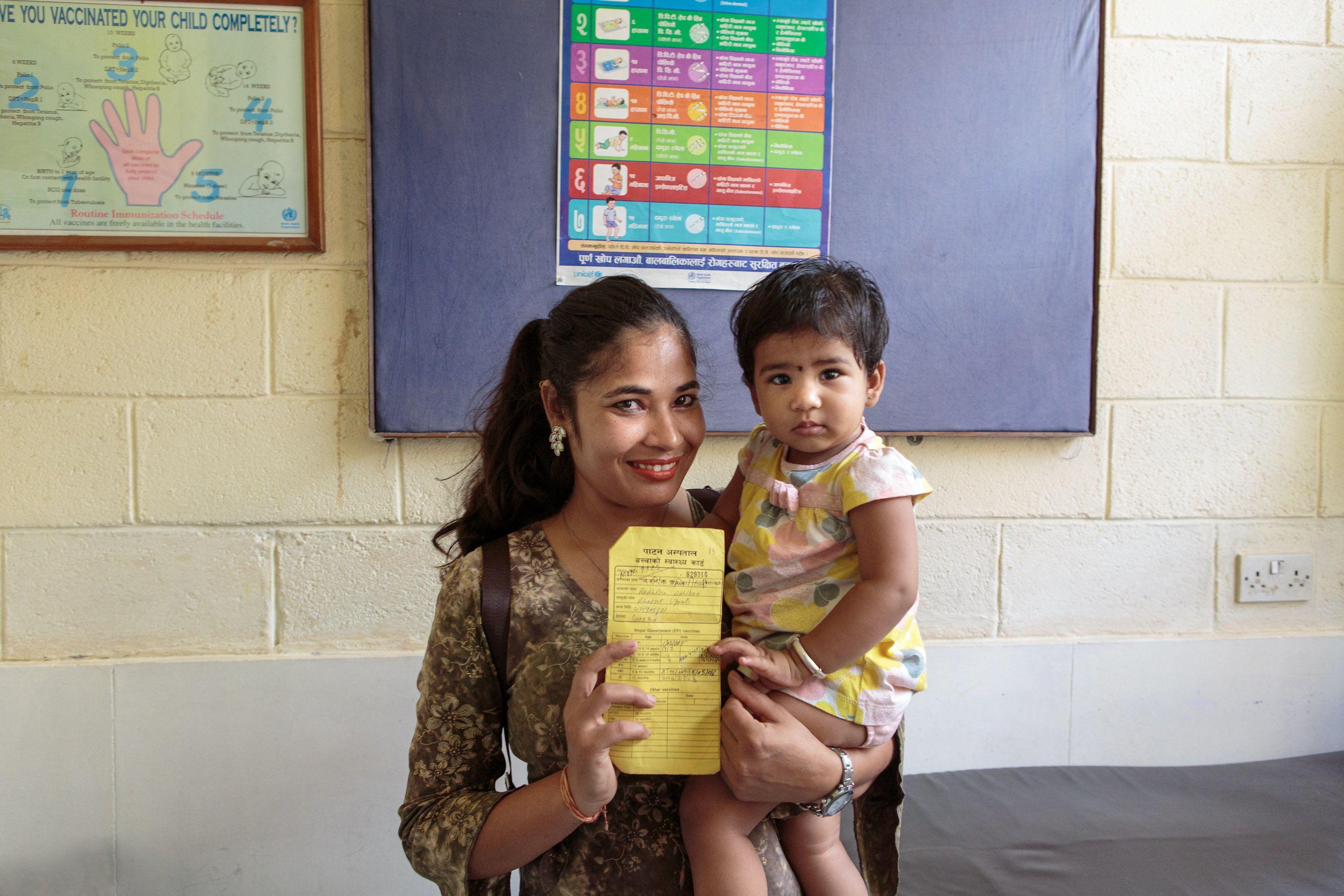

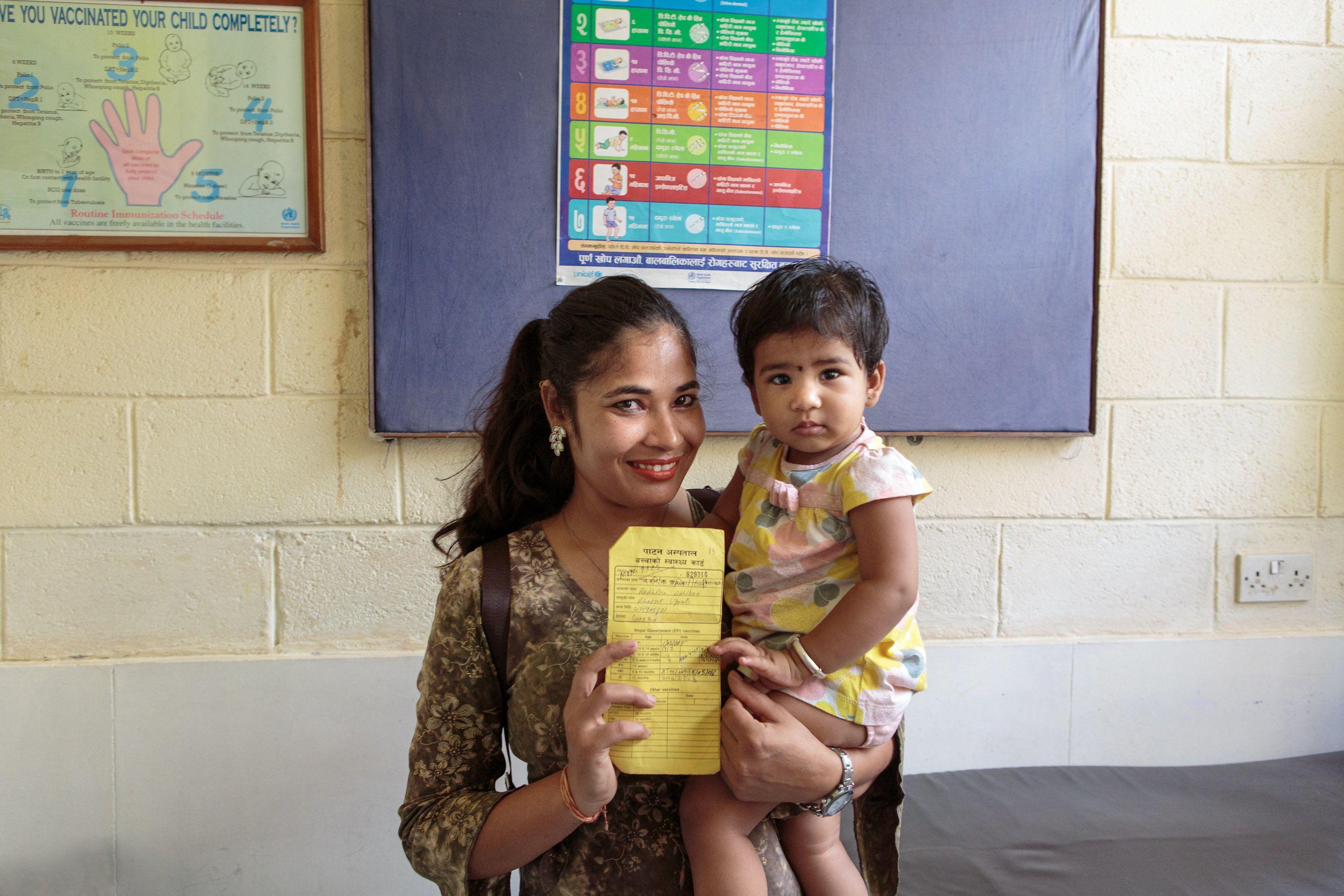

Sparshika sits on her mother's knee as her mother and a nurse review Sparshika's vaccine records. She's 15 months old and will receive a 2nd dose of measles-rubella vaccine today. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Downstairs in the Patan Hospital paediatric screening area sits Sparshika, a 15-month old reason for Nepal’s growing success against measles. Young Sparshika’s mother, Radhika, reviews her daughters’ vaccination history with a nurse. Sparshika is up to date with her vaccinations, and today it’s time for her second dose of measles-rubella vaccine.

Radhika carries Sparshika to queue at the vaccination room. Rows of parents and children wait on benches outside, while the nurse in the room works efficiently to attend to each child. In Nepal, the demand for vaccination is high.

“Nepalis know how important vaccines are,” says Professor Dr Shrestha. “During the conflict period in the mid-1990s, immunization services continued. Everyone knew the population would be unhappy if vaccination was stopped.”

The Goal: Eliminate Measles and Rubella

Measles, which can travel through the air on infected droplets from person to person, is one of the most infectious viruses on the planet. One person with measles could infect up to 18 other people if they weren’t already immune.

The virus can also be deadly for young children, particularly those who are malnourished or have weaker immune systems. Globally, measles and its complications killed about 545, 000 people – mostly young children - in 2000.

Since then, measles vaccination has prevented more than 21 million deaths globally. 1

The measles vaccine is very effective. One dose confers at least 85% immunity. With two doses, almost 100% of children are fully protected. Because the virus is so infectious, achieving high coverage with that second dose of measles vaccine is critical to ‘eliminate’ measles – to reduce measles cases to zero in any given country. The WHO South-East Asia Region has recently committed to eliminating measles by 2023. Nepal is working towards this goal.

In 2003, more than 5,000 Nepali children became sick with measles. At that time, measles vaccine coverage was about 75% and no second dose was given - far from the 95% coverage required with two doses of measles vaccine.

Professor Dr Imran Ansari examines a child with pneumonia at Patan Hospital. He says the fact there are so few measles cases frees up resources to treat children for other illnesses. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Nepal introduced a 2nd dose of measles-containing vaccine into its regular schedule in 2015. When a vaccine is in the official schedule, it’s offered across the country free-of-charge.

In 2018, just 260 cases of measles were confirmed in Nepal – representing a massive drop in cases, putting measles elimination in clear view.

“Not only do we rarely see measles cases here in the hospital,” says Professor Dr Ansari, “we don’t see the longer-term complications either.” “We have more resources to treat children for other conditions.”

And there’s more. Nepal introduced rubella vaccine as part of a combined measles-rubella or “MR” vaccine in 2013 in its routine immunization programme and carried out a wide age range campaign in the same year. Rubella generally causes a mild illness – but if a pregnant woman is infected, it can cause serious issues for the baby developing in the womb. Rubella infection of a pregnant mother can lead to miscarriage or stillbirth, and lifelong ear, eye and heart conditions for the newborn.

Through vaccination, Nepal has now officially ‘controlled’ rubella, meaning rubella cases have dropped by more than 95% in 2017 as compared to 2008. There were only 34 cases in the entire country in 2018.

Nepal isn’t a very large country – it’s under 1000 kilometres long, around 200 kilometres wide from north to south and has a population of about 29 million people. It’s also not a rich country and is considered one of 47 “least developed.”

Yet Nepal prioritises primary health care for its citizens, including immunization. Through the Immunization Act, vaccines are free to all Nepalis.

The Himalayan nation also has some of the least accessible terrain in the world. Thousands of villages – some with just a few households – are perched up and down Nepal’s valleys and mountains, connected by steep, narrow footpaths.

Bringing in daughters, grand-daughters and baby cousins for vaccination at the Tathali health post in Bhaktapur district outside of Kathmandu. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Under Nepali health policy, each of those villages is meant to be fully immunized. Achieving “Fully Immunized” status is a kind of pact between the community, the government and the health workers to reach every child with all vaccines.

About twenty kilometres outside of sprawling Kathmandu city, the terrain changes, and one needs a sturdy vehicle to reach the villages that hopscotch up and down the hills. It’s August and the fields are bright green.

Basanta Shrestha is a Public Health Officer in the Family Welfare Division of Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population. Here he takes part in a routine immunization education session at the Thathali health post. National commitment immunization is a major reason for Nepal’s high vaccination rates. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Inside the Tathali health post, mothers, grandmothers, a few fathers, big sisters and babies listen as the senior health worker tells them about the benefits of vaccination and answers their questions.

Today senior health leaders from the Federal Ministry of Health and Population are present as well, together with senior ward health and political leaders. They each take turns to speak, congratulating the local health workers and community for using the primary health services, including vaccinating their children. It’s well-deserved praise.

Tathali has the distinction of being the first village in the Kathmandu valley to have achieved “Fully Immunized” village development committee status. That means every infant has had every vaccine offered by Nepal’s public health program.

Sarita Thapa is a driver of this success. She’s a “Female Community Health Volunteer” – instantly recognizable in Nepal with her bright double-blue sari. She’s one of more than 50,000 women across the country connecting her community to the health system. They’ve been called the backbone of the health system, the “Florence Nightingales of Nepal.” 2

“I wanted to be a nurse,” Sarita, 30, explains. “But I started a family early and put my further education on hold. I still wanted to serve the children of my community.”

Sarita Thapa, a Female Community Health Volunteer, holds a child who lives in Tathali. "I want to serve the children of my community,” she says. One way to do this is ensure parents know when to take the child for immunization. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Sarita could certainly still be a nurse. She knows her job inside and out – from the details of supporting women to have healthy pregnancies, to ensuring their children receive the care which helps them thrive.

She keeps a close eye on every baby born in her community. She helps to monitor their growth, provides supplements like vitamin A, gives counsel if they become sick, and reminds parents when to take children for immunization.

Sarita Thapa says she remembers measles from when she was a child but doesn't see cases anymore. "I know it's very dangerous," she says. "So, when I see a child with fever and rash, I report that to the health unit." (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Sarita remembers the measles from when she was young. “I didn’t know what it was then, but I know now it’s very dangerous for children.” She doesn’t see it anymore – but like Dr. Imran, the paediatrician in Kathmandu, she reports every time she sees a child who has fever and a rash -the marker for measles. This reporting helps to ensure that any potential measles case is investigated, and samples are taken for laboratory confirmation.

She talks about her role helping her community, Tathali, to demonstrate it was ‘fully immunized.’ Normally, she volunteers about three hours a day – already substantial for a volunteer job. “But for fully immunized status, we made a list of every single person in the community and their immunization status,” she explains. “Sometimes I spent three and four days just searching for one person.” She says her hard work paid off – Tathali was recognized in 2017 as having immunized all its children with all the vaccines in the national immunization scheme and Sarita says, “it was well worth it.”

Hem Lama, a vaccination nurse, explains a finer point of vaccination to assistant Ambika Pardel, as he prepares to vaccinate baby Sabin Magar. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Inside the Tathali vaccination room, Hem Lama prepares a vaccine as baby Sabin Magar look on. He’s careful and slow with each child – waiting for them to settle before administering a second vaccine. “I love my job,” he says. “I love serving my community.”

It’s this kind of passion for the work from volunteers and health workers that will keep Nepal moving towards measles elimination.

An uneven path

There is still some hard work to do. Coverage with the first dose of measles vaccine is at 90% or above in Nepal for several years in a row, barring a dip in the year after the devastating earthquake in 2015. However, the 2nd dose coverage sits just below 70%. Nepal has been working through a major change to its state and municipal administration – decentralising funds and responsibility to a newer system of local self-governance through urban and rural municipalities. The country is working to match the new administrative system with oversight and delivery of health services including immunization.

The last year in particular has shown how the measles virus will resurge wherever there are children insufficiently immunized in the world – whether in North America, Europe or South Asia. Raising measles vaccine coverage to over 95% will guard against outbreaks, wherever they originate.

A promising future

Radikha holds Sparshika's immunization card. With her second dose of measles-rubella vaccine, Sparshika's childhood vaccinations are now complete. (Photo credit: WHO SEARO / C. McNab)

Back at Patan Hospital in Kathmandu, 15-month-old Sparshika receives her second measles-rubella vaccine. Like most toddlers, she wasn’t terribly happy about the injection itself, but her mood improves, and she is smiling again moments after.

Her mother, Radhika is happy too, as Sparshika had now completed all of her routine childhood vaccinations. She’s protected against diseases like measles that used to result in child illness and death in Nepal.