Meningitis

Meningitis is a serious infection of the meninges, the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. It is a devastating disease and remains a major public health challenge. The disease can be caused by many different pathogens including bacteria, fungi or viruses, but the highest global burden is seen with bacterial meningitis.

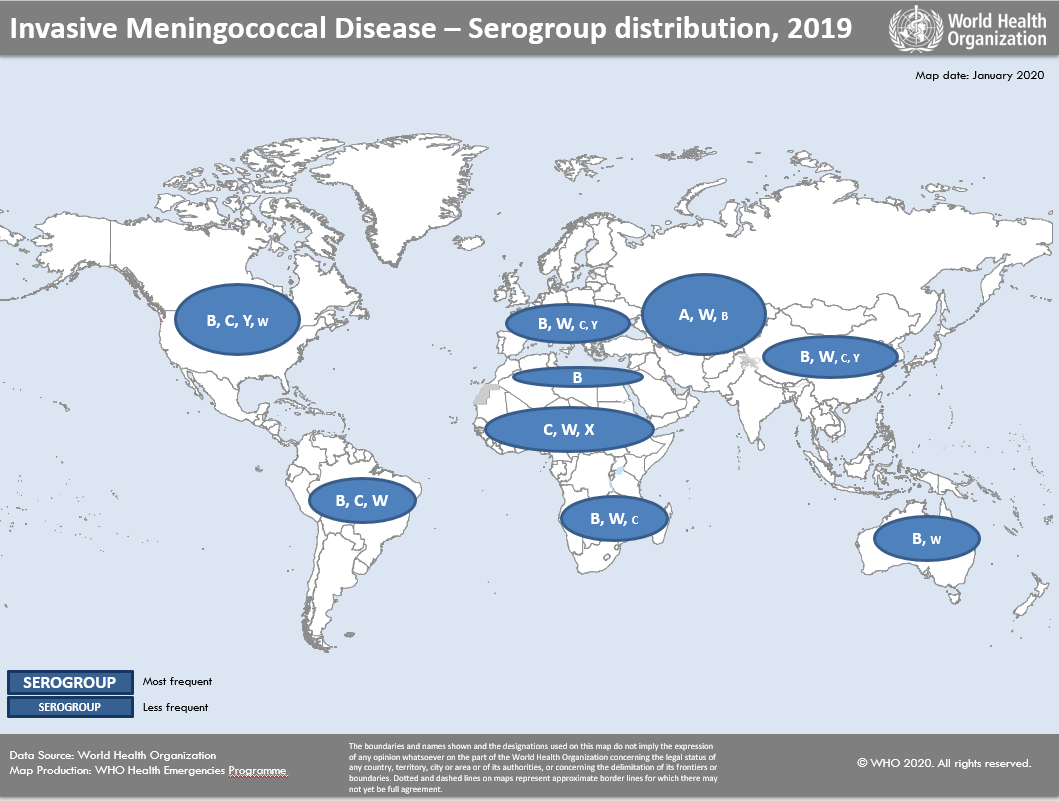

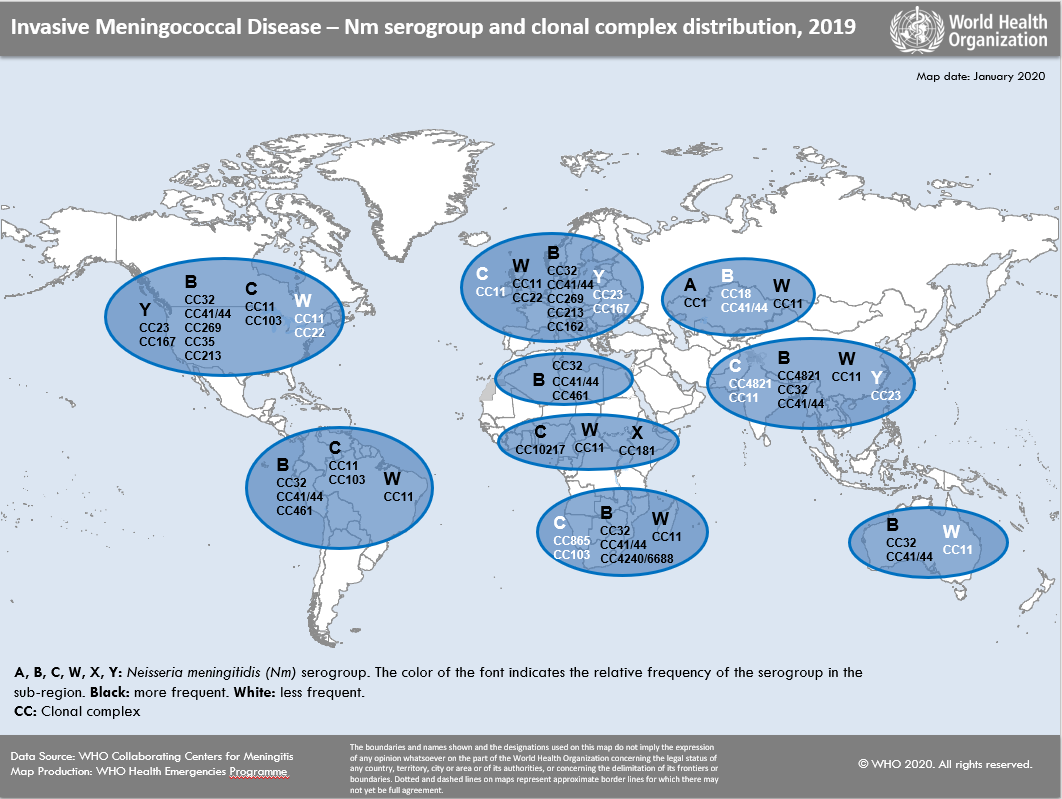

Several different bacteria can cause meningitis. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis are the most frequent ones. N. meningitidis, causing meningococcal meningitis, is the one with the potential to produce large epidemics. There are 12 serogroups of N. meningitidis that have been identified, 6 of which (A, B, C, W, X and Y) can cause epidemics.

Meningococcal meningitis can affect anyone of any age, but mainly affects babies, preschool children and young people. The disease can occur in a range of situations from sporadic cases, small clusters to large epidemics throughout the world, with seasonal variations. Geographic distribution and epidemic potential differ according to serogroup. The largest burden of meningococcal meningitis occurs in the meningitis belt, an area of sub-Saharan Africa, which stretches from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east.

N. meningitidis can cause a variety of diseases. Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) refers to the range of invasive diseases caused by N. meningitidis, including septicemia, arthritis and meningitis. Similarly, S. pneumoniae causes other invasive diseases including otitis and pneumonia

Transmission

The bacteria that cause meningitis are

transmitted from person-to-person through droplets of respiratory or throat

secretions from carriers. Close and prolonged contact – such as kissing,

sneezing or coughing on someone, or living in close quarters with an infected

person, facilitates the spread of the disease. The average incubation period is

4 days but can range between 2 and 10 days.

Neisseria meningitidis only

infects humans. The bacteria can be carried in the throat and can sometimes

overwhelm the body's defences allowing infection to spread through the

bloodstream to the brain. A significant proportion of the population (between 5

and 10%) carries Neisseria

meningitidis in their throat at any given time.

The most common symptoms of meningitis are a stiff neck, high fever, sensitivity to light, confusion, headaches and vomiting. Even with early diagnosis and adequate treatment, 5% to 10% of patients die, typically within 24 to 48 hours after the onset of symptoms. Bacterial meningitis may result in brain damage, hearing loss or a learning disability in 10% to 20% of survivors. A less common, but even more severe (and often fatal), form of meningococcal disease is meningococcal septicaemia, which is characterized by a haemorrhagic rash and rapid circulatory collapse.

Diagnosis

Initial diagnosis of meningococcal meningitis can be made by clinical examination followed by a lumbar puncture showing a purulent spinal fluid. The bacteria can sometimes be seen in microscopic examinations of the spinal fluid. The diagnosis is confirmed

by growing the bacteria from specimens of spinal fluid or blood, or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Diagnosis can also be supported by rapid diagnostic tests such as agglutination tests, although currently available tests have several limitations.

The identification of the meningococcal serogroups and testing for susceptibility to antibiotics are important to define control measures. For more guidance on diagnostic methods for meningitis see below:

Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae

Laboratory materials for the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Meningococcal disease is potentially fatal and is a medical emergency. Admission to a hospital or health centre is necessary and appropriate antibiotic treatment must be started as soon as possible. Appropriate antibiotic treatment must be started as

soon as possible, ideally after the lumbar puncture has been carried out if such a puncture can be performed immediately. If treatment is started prior to the lumbar puncture it may be difficult to grow the bacteria from the spinal fluid and confirm

the diagnosis. However, confirmation of the diagnosis should not delay treatment.

A range of antibiotics can treat the infection, including penicillin, ampicillin and ceftriaxone. Under epidemic conditions in Africa in areas with limited health infrastructure and resources, ceftriaxone is the drug of choice.

Vaccines and immunization

Licensed vaccines against meningococcal disease have been available for more than 40 years. Over time, there have been major improvements in strain coverage and vaccine availability, but to-date, no universal vaccine against meningococcal disease exists.

Vaccines are serogroup specific and the protection they confer is of varying duration, dependent on which type is used.

Since 2010, a meningococcal A conjugate vaccine has been rolled out through mass preventive immunization campaigns in the meningitis belt of sub-Saharan Africa, dramatically bringing down cases of the A serogroup.

There are three types of meningococcal vaccines available:

- Polysaccharide vaccines used in outbreak response, mainly in Africa

- Conjugate vaccines used in prevention and outbreak response.

- Protein based vaccine, against N. meningitidis B. It has been introduced into the routine immunization schedule (four countries as of 2020) and used in outbreak response

For more information on meningococcal vaccines and immunization.

For more information on the meningitis ICG vaccine stockpile.

Chemoprophylaxis

Giving antibiotics promptly to close contacts of a person with meningococcal meningitis decreases the risk of transmission.

- Outside the African meningitis belt, chemoprophylaxis is recommended for close contacts

- In the African meningitis belt, chemoprophylaxis for close contacts is recommended in non-epidemic situations.

Ciprofloxacin antibiotic is the antibiotic of choice, and ceftriaxone an alternative.