Working for better health

for everyone, everywhere

Good health is a precious thing. When we are healthy we can learn, work, and support ourselves and our families. When we are sick, we struggle, and our families and communities fall behind.

That’s why the World Health Organization is needed. Working with 194 Member States, across six regions, and from more than 150 offices, WHO staff are united in a shared commitment to achieve better health for everyone, everywhere.

Our guiding principle

The principle that all people should enjoy the highest standard of health, regardless of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition, has guided WHO’s work for the past 70 years, since it was first set up as the lead agency for international health in the new United Nations system.

Over the years, people have come together to reiterate and reinforce this principle — for example in the Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978, which set the aspirational goal of health for all. It remains front and centre today, in the drive for universal health coverage.

used in well over 100 countries and has been

translated into more than 40 languages.

Producing standards

From the very beginning, WHO has brought together the world’s top health experts to produce international reference materials and to make recommendations to bring better health to people throughout the world.

These range from the International Classification of Diseases, which enables all countries to use a common standard for reporting diseases and identifying health trends, to the WHO Essential Medicines List — a guide for countries on the key medicines that a national health system needs.

WHO’s work has led to global standards for air and water quality, so important in a world where pollution is an increasing threat to our health; safe and effective vaccines and medicines, thanks to its prequalification programme; and height and weight charts for children, to guide health professionals and parents in helping young people grow up healthy and strong. It has also led to guidelines and advice on preventing and treating health conditions ranging from asthma and hepatitis to malnutrition and Zika.

for parents to bring their children to health

centres from the earliest age.

Making a difference on the ground

But WHO doesn’t just make recommendations – it helps countries use them to keep more people healthy. For decades, WHO staff have worked alongside governments and health professionals on the ground. In the early years, there was a strong focus on fighting infectious killers like smallpox, polio and diphtheria. The Expanded Programme on Immunization, for example, set up by WHO in the early 1970s, has, with the help of UNICEF, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and others, brought lifesaving vaccines to millions of children.

In the last century, access to antibiotics, clean water and improved sanitation became powerful weapons in preventing infectious disease. A real challenge now is to protect the effectiveness of antibiotics, through a global programme to fight antimicrobial resistance, and to ensure that the entire world benefits from safe water and sanitation to prevent infections occurring in the first place. Today, access to clean drinking water and safe sanitation facilities is one of the most obvious examples of the stark divisions between rich and poor.

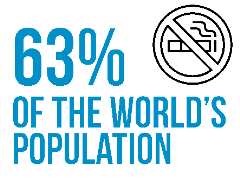

by at least one comprehensive tobacco control

measure, such as graphic warnings on cigarette

packs, advertising bans or smoke-free laws.

Shifting focus

In recent decades, the world has seen a rise in noncommunicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease. Driven by forces such as rapid unplanned urbanization, globalization of unhealthy lifestyles and population ageing, these diseases now account for 70%of all deaths. So WHO has shifted focus, along with health authorities around the world, to promote healthy eating, physical exercise and regular health checks.

The Organization has run global health campaigns on the prevention of diabetes and high blood pressure and on healthy cities. It negotiated the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a formidable tool to help reduce disease and death caused by tobacco.

But these are not the only forms of noncommunicable illness. Mental health is a major issue around the world. WHO has helped extend mental health care in more than 110 countries. This is thanks in part to training nonspecialists and increasing mental health and psychosocial support for people affected by natural disasters and conflict.

At the same time, work has ramped up in areas such as violence and injury prevention, highlighting the devastating consequences of maltreatment of children, sexual violence and elder abuse, as well as road traffic accidents and drowning. And WHO has called attention to the importance of catering to the needs of people with disabilities, through strengthened rehabilitation services in health programmes and better access to assistive technologies.

interactive repository of health statistics,

from which data on specific health topics,

at country, regional and global levels, can

be viewed, downloaded and shared.

Using data to target our efforts

Tracking progress in all of these areas requires a strong monitoring system. Data collected from countries across the world is stored in and shared through WHO’s Global Health Observatory. This powerful tool helps countries get a clear picture of who is falling sick, from which disease, and where, so that efforts can be targeted where they are needed most.

The ability to collect and analyze data has been critical to WHO’s work to improve health through the life-course – from before birth right through to the last years of life. This approach, with its focus on critical periods such as pregnancy, early childhood, and adolescence, emphasizes the importance of getting a healthy start in life, and of making the extra effort to reach people who might otherwise get left behind – all too often, women and girls living in the poorest environments.

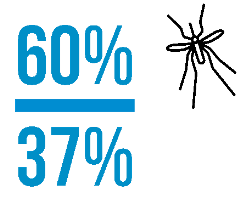

and tuberculosis deaths by 37% between 2000

and 2015 as a result of expanded prevention,

diagnosis and treatment.

Progress on many fronts

WHO has much to be proud of.

Globally, life expectancy has increased by 25 years since 1950. In 2016, 6 million fewer children died before they reached their fifth birthday than in 1990, smallpox has been defeated and polio is on the verge of eradication. Many countries have successfully eliminated measles, malaria and debilitating tropical diseases like dracunculiasis (guinea worm) and lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis), as well as mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis.

Bold new recommendations for earlier, simpler treatment, combined with efforts to facilitate access to cheaper generic medicines, have helped 21 million people get life-saving treatment for HIV. The plight of more than 300 million people suffering from chronic hepatitis B and C infections is finally gaining global attention. And innovative partnerships have produced effective vaccines against meningitis and Ebola, and the world’s first ever malaria vaccine.

record, killing more than 200 people.

WHO released US$ 1.5 million from

its Contingency Fund for Emergencies

to boost the response.

On constant alert

Every year, WHO studies influenza trends, to work out what should go into the next season’s vaccine. And it remains on constant alert against the threat of pandemic influenza. One hundred years after the flu pandemic of 1918, WHO is determined that

the world should never again be subjected to such a threat to global health security.

In 2005, WHO released updated International Health Regulations, to help the international community prevent and respond to acute public health risks that have the potential to cross borders and threaten people worldwide. The tool is as important today as it has ever been.

WHO’s renewed commitment to prevent outbreaks from turning into epidemics, and to respond better and faster to humanitarian emergencies, has spurred the creation of a new health emergencies programme that works across all three levels of the Organization. With a major focus on watching out for early warning signs, and helping countries get prepared, WHO is setting up systems to get help where it’s needed, when it’s needed. Recent successes include containment of outbreaks of plague and Marburg virus disease, and helping lead major cholera and yellow fever vaccination campaigns.

Working towards the Sustainable Development Goals

Today, WHO works alongside a host of health and development partners to achieve the health-related targets laid out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs underscore the key role health plays in assuring the world’s future, with SDG3 calling on all stakeholders to “ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages”. And they align totally with WHO’s goal of ensuring that everyone, everywhere, can realize their right to a healthy life. They also stress the importance of collaboration, between different actors working in different fields, in all countries of the world.

With an eye set firmly on 2030, WHO will build on the lessons learnt over its first 70 years. This experience, plus its networks and partnerships — at global, regional, national and local levels — will be critical to ensuring good health and wellbeing for all.

Working smarter

But this alone will not be enough. If WHO is to further increase its impact on global health, it must step up its work with the highest levels of government to ensure that health is placed firmly on political agendas. It must strengthen leadership in the areas where it adds most value, and streamline the way it does business to work smarter, for quicker results.

The mission, as articulated in WHO’s new General Programme of Work is to “Promote health, keep the world safe, serve the vulnerable”. It is proposing ambitious new targets to be achieved by 2023: 1 billion more people benefitting from universal health coverage; 1 billion more people better protected from health emergencies; and 1 billion more people enjoying better health and wellbeing.

Achieving these goals will require unfailing political and financial commitment, from Member States and donors, and continued and expanded collaboration with colleagues from academia, partners on the ground, and other members of the UN family.

Success will be driven by a shared commitment, as deep now as ever before, to build a world where all people, everywhere, have access to quality and affordable health care. Our guiding principle of health for all remains as relevant now as it was when our Organization was founded, 70 years ago.